This week, I will explore the importance of new variables to predict the two-way popular vote within contentious states in the presidential election. Key factors include incumbency measures, federal spending, and expert prediction. I finish with my new prediction using super learning.

Historical Analysis of Incumbency

The incumbency status of a party or candidate influences their perception by the electorate and their popular vote outcome, as mentioned in past weeks. The core question is in the mechanism behind the incumbency advantage: is it reflective of the incumbent president alone or benefits the party in general?

Analyzing presidential elections since 1952, I aggregate the results of incumbent candidates and parties to see who benefits. Of 18 elections, only 33% re-elected a sitting president. However, among 11 elections with incumbents, 63.64% won. In the 6 elections since 2000, three of four incumbents were re-elected, with Donald Trump as the exception.

While incumbent presidents show a greater-than-random chance of re-election, incumbent parties present a different narrative: they have lost 10 of the last 18 elections, and only 27.78% won when filtering for candidates from the previous administration.

Incumbency Advantages and Disadvantages

Diving deeper into the incumbency advantage source, I explore institutional factors that may impact an election in their favor. These include:

- Bully Pulpit: can shape public opinion and have media attention

- Campaigning: have a continuous campaigning advantage

- Party Nominations: challengers fight for nomination while incumbents conserve resources

- Powers of the Office: can control spending to win favor with constituent

- Pork Barrel Spending: can target certain districts

While these are theoretically significant, empirical evidence remains limited. Presidential spending on disasters has some empirical evidence of impact at the presidential vote level.

According to Brown (2014), the electoral advantage typically linked to incumbents arises more from structural factors than from voter preferences. Brown’s randomized survey experiment showed that, when controlling for these structural advantages, voters display minimal preference for incumbents over challengers. Furthermore, partisanship, rather than incumbency, shapes voter preferences, with no significant evidence of incumbency fatigue or diminishing support for long-serving incumbents.

Incumbency also has theoretical disadvantages, including that polarized electorates lead partisanship to matter more as in Donovan et al (2019). Recessions and disasters are also blamed on incumbents, per Achen and Bartel (2016). Incumbency fatigue, though disproved in Brown’s study, may need to further study on its influence in this election specifically.

In 2024, it seems acceptable to assume that the impact of incumbency for both candidates may be negligible or cancel each other out.

Historical Impact of Federal Spending

Is federal spending something I should use to predict popular vote outcomes? The answer is no. Kriner and Reeves (2012) find that increased federal spending boosts electoral support for incumbents, especially in battleground states. Federal grants serve as “electoral currency,” particularly where congresspeople align with the president’s party. However, the benefits of spending vary, with liberal/ moderate voters rewarding presidents more than conservatives, highlighting the nuanced role of federal spending in electoral outcomes based on partisan dynamics, voter ideology, and electoral context.

My analysis focuses on the distribution of federal/pork spending over time: whether presidents propose equitable budgets (universalism), reward co-partisans (partisanship), or target electorally important constituents (electoral particularism).

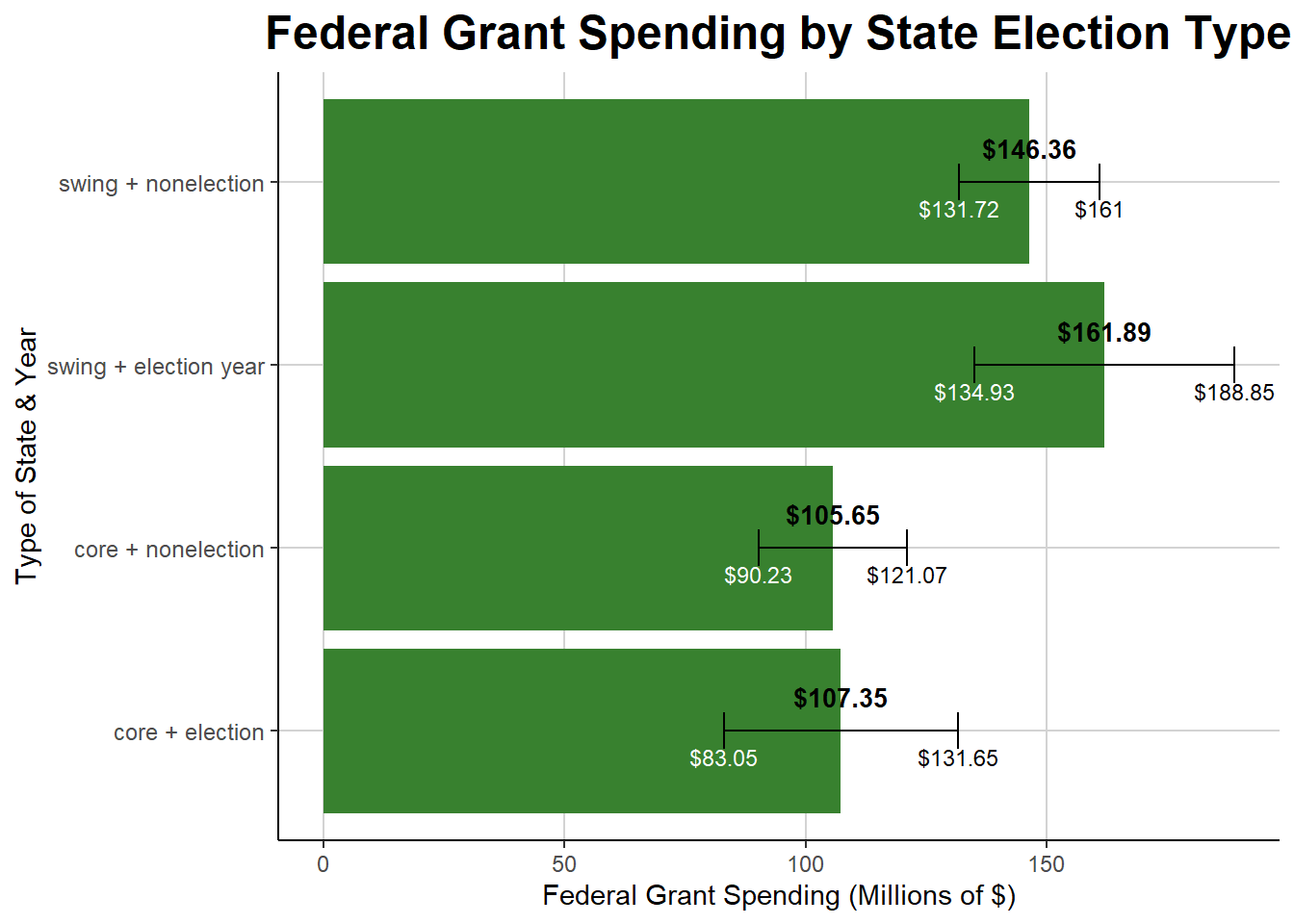

Note: core states are where the president has a large number of co-partisans.

Within each state group, spending across years is not statistically-significantly different, indicating that presidents don’t spend more in election years or that the budget takes time. However, between swing and core states, the difference is statistically significant; presidents spent more in swing states on average 1988-2008, supporting that the budget is used to influence competitive states. Additionally, incumbents do not spend significantly more when they versus their successors are running. This means Harris will likely not have different spending than Biden would as candidate.

Running regressions to predict popular vote outcomes based on the interaction between federal grant spending and votes, including year fixed effects, does not do well on the state level and is not useful for my final prediction model.

Expert Prediction Accuracy

A more promising variable is expert predictions from organizations like the Cook Political Report and Sabato’s Crystal Ball, which rate states on a 7-point scale for competitiveness, ranging from strong democrat (1) to strong republican (7) victory likelihood.

In 2020, they agreed on 42 states, including DC. Their disagreements were mostly on level of confidence, though in the case of Georgia, Minnesota, New Hampshire, and North Carolina one rated it a toss up but the other a swing to one party. Overall, their predictions are very similar, and have become closer each year since 2004, when they had 65% matches.

Cook’s accuracy in 2020 was 88.2%, while Sabato’s was 98%. Notably, Sabato had no toss-ups, which affects their accuracy assessment. Cook has 6, all from rating states as toss-ups bearishly and therefore marked automatically incorrect. Sabato only missed North Carolina. If we did not count toss-ups as wrong, Cooke would have 0 incorrect predictions to Sabato’s 1. In this way, they have similar accuracy in 2020.

Below I evaluate predictions using a numerical method, assessing how well experts performed in each state beyond simple correct/incorrect counts. I create a numerical method 0 to 1, 1 meaning good certain prediction (rated as strongly going to a party and it does) and 0 meaning incorrect certain prediction (rated as strongly going to a party but it goes to the other). In the future, I would add another dimension for ratings matches.

As shown above, both expert predictions did extremely well in 2020 predictions. Their predictions appear reliable, especially for moderate-strong states. With this in mind, my state-level model will be built only in states deemed competitive in the 2024 election by expert prediction.

Both Sabato and Cook identify the same seven critical toss-up states for 2024: Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. Cook has one lean-democrat, Nebraska’s second district, but polling information may not be available. These are the states I will focus on going forward. This gives us a starting point of 226 Democratic and 219 Republican electoral votes.

This Week’s Prediction Using Super Learning

Because this week focused on understanding additional variables, my final prediction is a super-learning version of last week’s ensemble model of polling and economic fundamentals, only from swing states.

| State | D Pop Vote Prediction | Winner |

|---|---|---|

| Wisconsin | 52.277 | D |

| Virginia | 54.681 | D |

| Texas | 49.352 | R |

| Pennsylvania | 50.596 | D |

| Ohio | 46.866 | R |

| North Carolina | 49.832 | R |

| New York | 61.19 | D |

| New Hampshire | 53.933 | D |

| Nevada | 50.815 | D |

| Minnesota | 51.821 | D |

| Michigan | 51.114 | D |

| Georgia | 50.206 | D |

| Florida | 50.004 | D |

| California | 61.701 | D |

| Arizona | 50.292 | D |

The results from the super-learning model for the states identified from expert prediction are in green.

Current Forecast: Harris 303 - Trump 235

Data Sources

- Polls, State and National, 1968-2024

- Popular Vote and Incumbency, State and National, 1948-2020

- FRED Economic Data

- Federal Grants, State and County, 1988-2008

- Cook Political Report Ratings, 1988-2020

- Sabato’s Crystal Ball Ratings, 2004-2024