This week, I shift my lens through which I evaluate the presidential election away from fundamentals to explore how campaign effects could be useful in on refining my model. Starting with the Air War, the advertising arm of the campaign effort, I use descriptive statistics to explore trends in spending across states, media markets, and digital platforms. I also dive into FEC funding data. Finally, I discuss literature and implications of campaign effects for my forecasting effort. Consistent with my decision to focus on select states from last week, I will be sure to note specific trends in Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, North Carolina, Nevada, Michigan, Georgia, and Arizona.

Descriptive Statistics on Campaign Ads Over Time

Thanks to the Wesleyan Media Project, data on the ads run by each campaign 2000-2012 and 2020 are available to understand the content, geographic impact, and spending of campaigns on TV ads, and Facebook ads in 2020. In campaigns that consistently spend hundreds of millions of dollars on advertising, understanding where they are targeting and at what scale may be helpful to understand if their actions have any impact on the outcome of the election. The actual usefulness of measures of advertising volume and spending will be further explore below, but it is worth noting that up until now fundamentals including polling and economic forces– which campaigns cannot control– have been doing well in their in-sample predictions of past elections without the inclusion of any campaign factors.

Diving into the data from Wesleyan Media Project, we see that the various datasets include helpful indications of how each campaign is implementing their ads. In the first dataset with basic advertising information 2000-2012, information including the air date, party, sponsor/ candidate, state, creator, number of markets and stations where it played, total cost, and indicator for it occurring before or after the primary are included. Another set for the same years includes the main issue of each ad, whether it was personal or policy focused, and what its tone was.

Different, higher level information is also available for 2020, focusing on how many ads each candidate aired between certain dates in each state, as well as the total amount of money spent in that state, which is unfortunately not broken out by candidate. When I evaluate this dataset, I will have to use airing as a proxy for money spent, which within each state seems to be a moderately strong assumption by correlation. Data for Facebook ads in 2020 are also available.

As I work through descriptive analyses with these data, I will point out potential issues and inconsistencies that would make more granular measures of the effect of different issues or types of ads difficult, but in this case the data are not available to make predictions on this anyways. The only data which I can carry forward to 2024 that is being added to the analysis today is FEC spending data, which will be evaluated in the next section.

Beginning with the data on the characteristics of these ads, I look at the distribution of tones since 2000 and how it has changed.

Note that from 2000 to 2012, there have only been four presidential elections, so judging the trend of which tone of ad is becoming most popular will be fraught. However, the differences between the parties may hold interesting insights. While the exact percentage of each type of ad varies between parties within a year, the increase of decrease in popular of a tone appear to be consistent between parties across years. This is not the case with the “promote” tone advertisements from 2008 to 2012, as Democrats nearly doubled the number of ads of this type between those cycles while Republicans cut their amount. The Democrats had also had a very small amount of ads promoting the candidate in this way in 2008, but Republicans still see a decrease in this tone between each election cycle, in 2012 in favor of a nearly 61% share of attack ads, the largest share of attack ads above.

As another caveat to any trends above, these data may reflect the climate of each election rather than any long term terms. Additionally, these are hand coded with only one value per ad, and the thresholds between categories may not be consistently applied across all viewers. These potential misunderstanding between hand coders of ads could lead to issues in interpretation here and in later sections as well, especially when it comes to encoding a single issue that each ad takes on.

Now, I plot the purpose of each advertisement across years.

Once again, it is hard to draw any exact trends off of so few election years, but it is common for policy ads to dominate the airwaves. It appears that the outlier in the above trend is 2016 for the democrats, when the number of personal ads was extremely high compared to any other year. This may be due to the opponnent, Donald Trump, and could have been both positive and negative ads. Because 2016 data was manually entered, I cannot directly explore this.

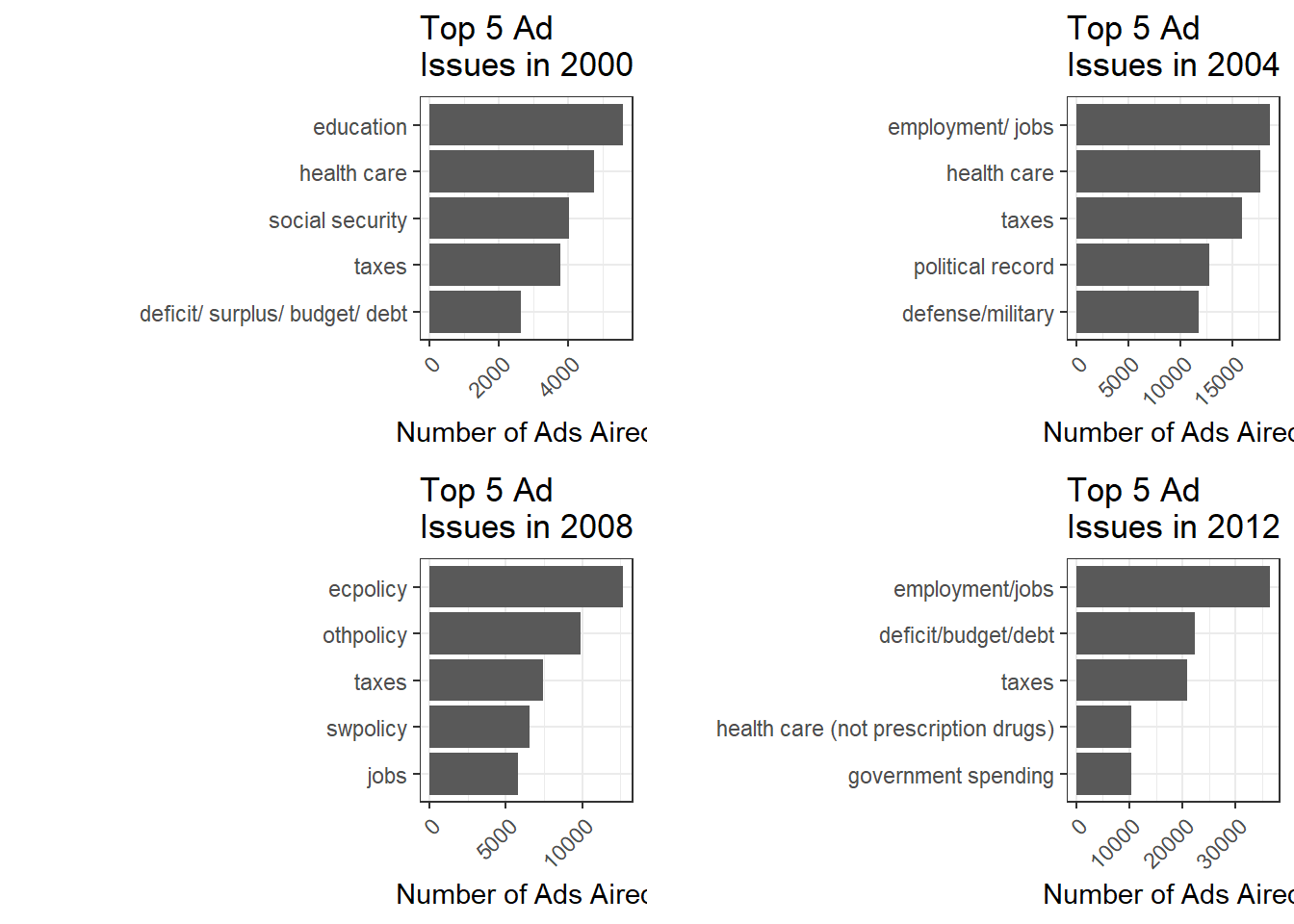

These ad categories are often quite counter intuitive, with healthcare, healthcare (not prescription drugs), and prescription drugs all existing, but unclear as to how they were distinguished. Similar issues are apparent in other areas, and not consistent in categorization across years. While it is interesting to see above which areas and issues were most important, it will not be used in my model specifically.

I will look more specifically at all issues in ads split by party below. I then use my best judgement to group each issue into a much more broad category to understand if there are any higher level patterns in issue engagement for each party. I start with 2000 below.

While this may be informative on which specific issues a campaign may favor, I have grouped these issues below into broader categories to see if the patterns are still very different by topic for each party

This plot allows me to see that even aggregating up into categories of issues, the different issues that the parties choose to advertise on remains. While these issues may vary slightly from their party affliations today, they do not seem all too different.

I will also look at this aggregation of issues for the years 2000-2012.

It is interesting to see how many issues democrats dominated on in 2004, whereas most other years each party has an issue or two on which they have the sole focus. With these larger categories, I can see how issues like child care remain strong democratic issues while Middle East conflicts has shifted. This can be observed across many of the issues above as party attitudes and platforms change.

These descriptive statistics have allowed us to see that campaigns as a whole change quite a bit in their focus and tactics over time. It is worth noting, however, the while the underlying tactics may not be useful for prediction, the gross volume of ads could be, which is data we have.

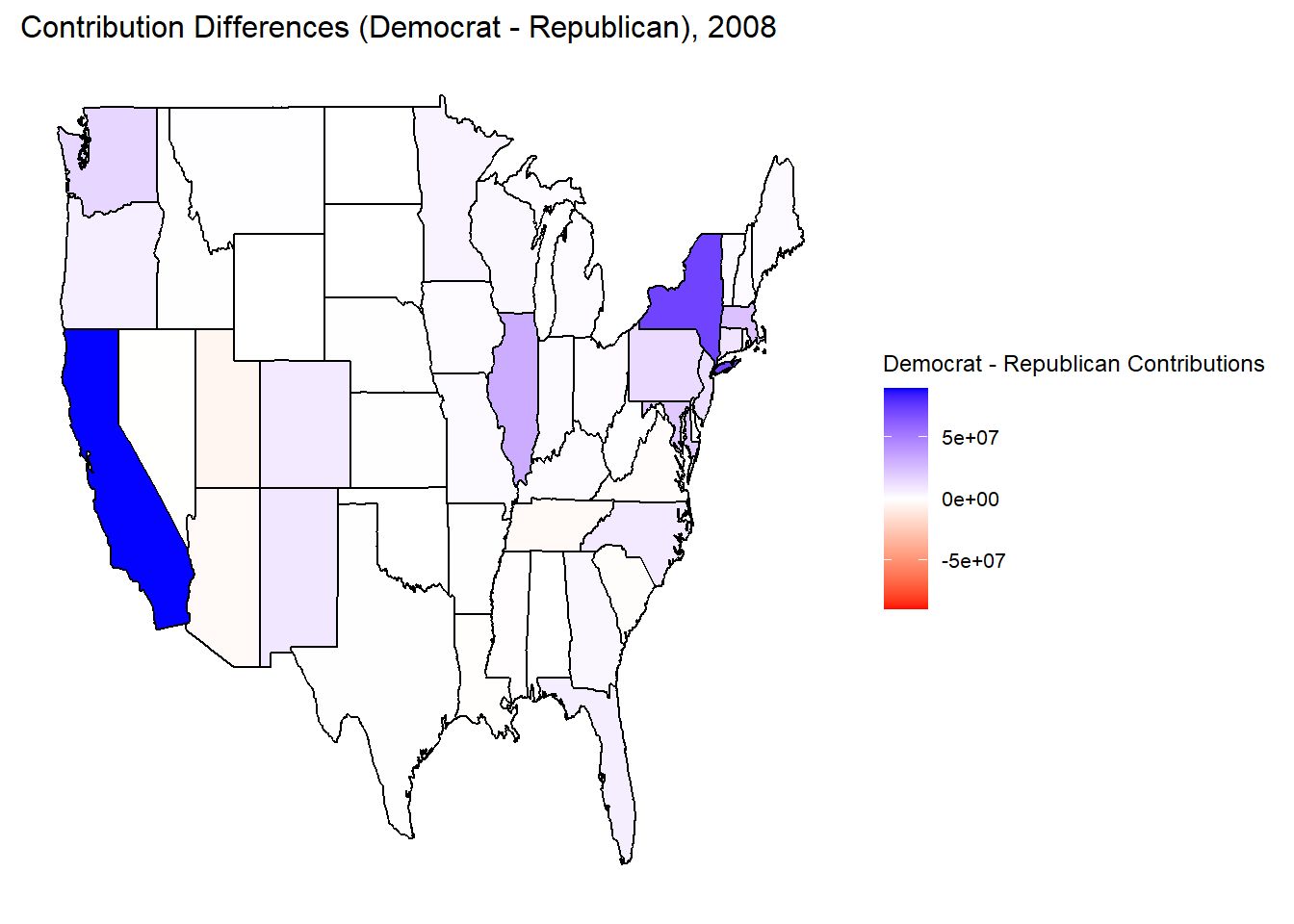

FEC Contributions by state

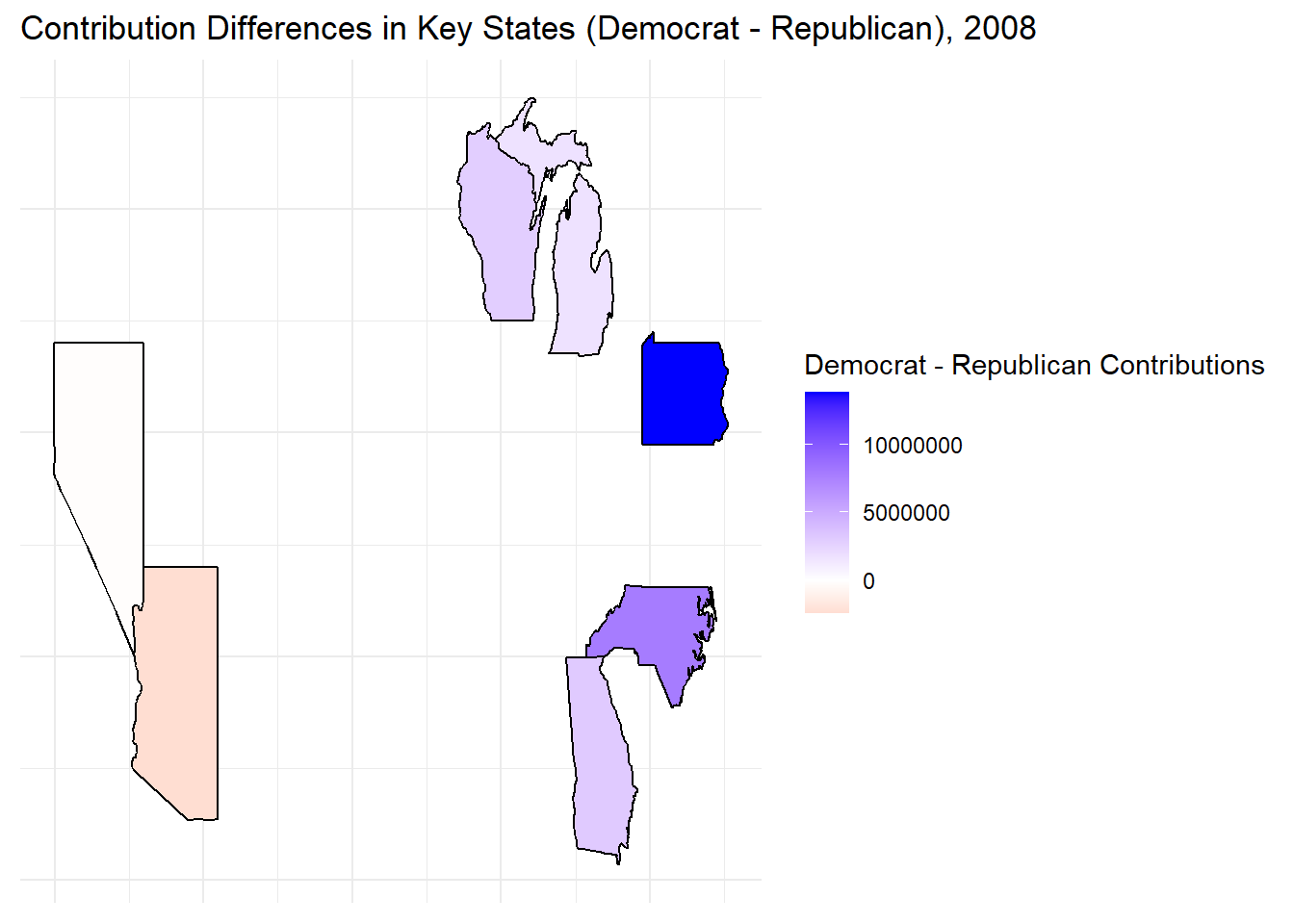

Because some Democratic states have such large contributions to the campaign, it makes it difficult to tell what the contributions are in other states. Looking only at my states of interest, this becomes more clear.

I can also look at this specified state map for 2012, 2016, 2020, and even 2024.

The 2024 spending map does not look dominated by either party as past years’ spending maps have been. Additionally, the amount of outspending appears to even out across the two parties, whereas in years like 2016 the axes and spending differences are very skewed towards the Democrats. Though this is just descriptive exploration, I wonder how contributions and funding could be used in my model on a state level, and have therefore considered adding it to see how it impacts in sample fit. I could also test its predictive ability alone. Note that this is not the same as advertising spend, a value I do not have access to for 2024.

Campaign Effects Versus Fundamentals

Campaign advertising, or the “air war,” is central to modern campaign strategies, potentially significantly shaping voter turnout and voting decisions. Historically, the effectiveness of campaign advertising has been debated. Memorable ads, such as Lyndon B. Johnson’s 1964 daisy ad and George H.W. Bush’s Willie Horton ad, showcase the powerful impact of emotional messaging.

To attack the impact of advertising, I focus on volume because if the volume won’t matter, then the content won’t matter. This provides color to the descriptive analysis above as fading in comparison to the actual numbers of ads pushed out and spending done on it.

Campaigns spend hundreds of millions of dollars on advertising for TV alone, pointing to it having a significant impact on voter decisions. It is the largest single line item for most campaigns, having both a persuasion and a mobilization effect. Go assess the durability of campaign ads, Hill, Lo, Vavreck, and Zaller (2013) undertook panel studies that showed that advertisement effects do exist but fade away after a short lifespan of hours or days. This was also seen in Gerber, Gimpel, Green, and Shaw’s 2011 experiment with the Rick Perry campaign for governor of Texas, where advertisements could actually be randomized.

Huber and Arceneaux (2007) have also studied the effect of campaign ads using a natural experiment of the NH/ MA media market. As New Hampshire is an important state to win while Massachusetts is not, comparing the voting patterns of MA residents who see campaign ads versus those who don’t isolates the effect of the commercials, as no other campaigning takes place in Massachusetts. They saw large persuasive effects on voters, indicting that campaign commercials cumulatively do have an effect on voter decisions and those hundreds of millions may not be a waste.

Though I would be interested in including advertising directly in my model, I do not currently have the data to do so for 2024.

Prediction

Due to space constraints, I will be sticking with my prediction from last week. However, in the next week’s prediction, I plan to add in contributions as reported by the FEC as a variable to see if it increases the in sample fit of my model. If it does, it will be included in the simulations of the outcome. I will also be using MCMC next week to compare my model to a Bayesian model with the same variables of average poll value, most recent poll results, economic fundamentals, and now contributions. With no difference to report for my prediction, I hold at

Current Forecast: Harris 292 - Trump 246

Data Sources

- Popular Vote Data, national and by state, 1948–2020

- Electoral College Distribution, national, 1948–2024

- Turnout Data, national and by state, 1980–2022

- Polling Data, national and by State, 1968–2024

- Wesleyan Media Project, campaign ads and creative ads, 2000-2012

- Wesleyan Media Project, ads and facebook ads, 2020

- FEC Campaign Spending, 2008-2024